When I began crafting The Cedar Tree, I wanted to explore the idea of what it means to be free; individually, as a community, a society and, ultimately, as a country. How far an individual is willing to go to obtain their liberty is matched only by the cost associated with gaining that freedom. And then there is the very real question of what happens afterwards. Can a person ever truly begin their life again?

Selecting two time periods, the 1860s and the 1940s, and distinct locations, Ireland, the NSW Richmond Valley and the Strzelecki Desert, allowed me to tell the story of the Irish O’Riain family from when they first flee County Tipperary as wanted criminals in the 1860s, through to Italian Stella Moretti’s marriage into the O’Riain family during World War Two and her eventual life on the fringes of the Strzelecki Desert.

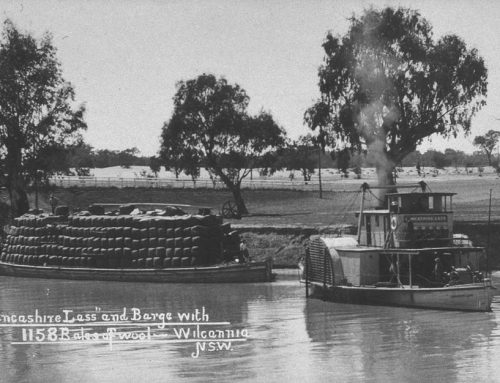

(Photo taken at Mid-Richmond Historical Society – Coraki.)

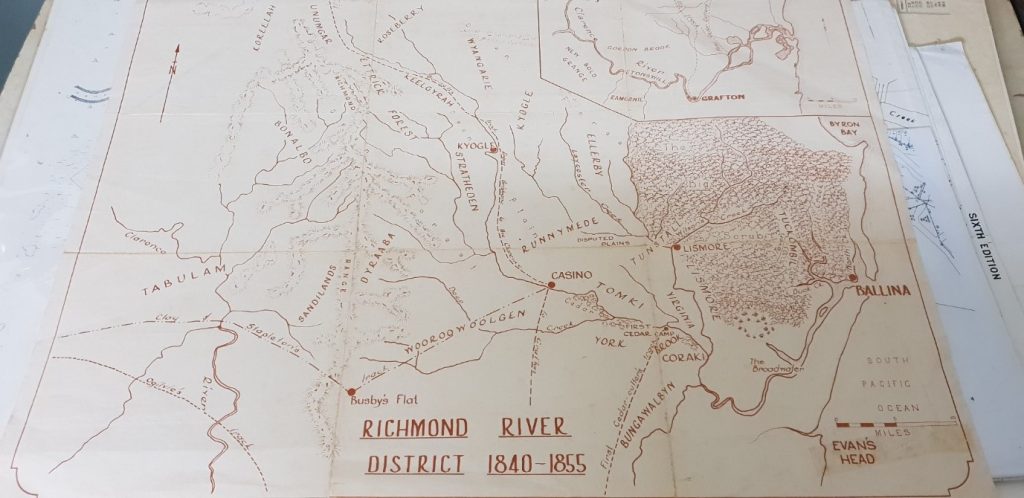

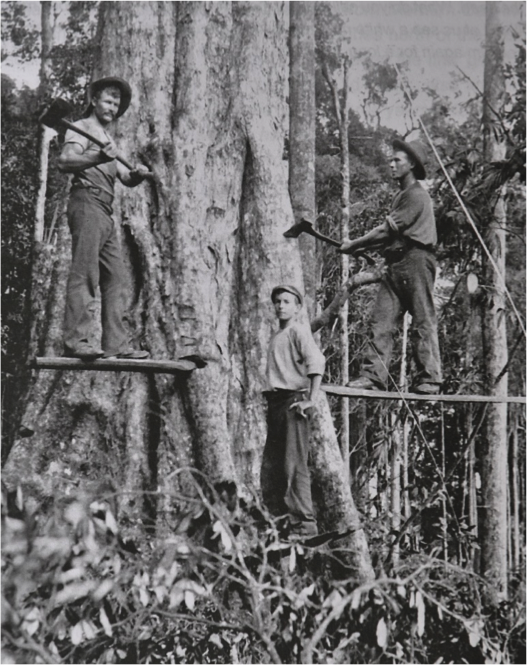

In 1867, after feeling Ireland, Catholic Irish cousins Brandon and Sean O’Riain are working as cedar-cutters in ‘The Big Scrub’ in the lush Richmond Valley, where they try and find a place for themselves among pastoralists, servants, and labourers as Fenian rumblings grow and rural land disputes escalate. My background research included discovering the rich history of the cedar-cutting industry. These intrepid axe-men scanned the newspaper reports of the day and followed the journeys of our earliest surveyors and explorers, knowing that the brilliantly coloured red cedar that was coveted by the Royal Navy, furniture-makers, and ship and house builders, could often be found near waterways. Their fortitude places them as true pioneers in our history. And the timber industry is credited with the establishment of inland towns and the creation of a strong shipping industry. However, the demand for ‘red gold’ and other quality timbers decimated ‘The Big Scrub’. Located between Byron Bay, Ballina and Lismore this strangely named area was, at 75,000 hectares pre-European settlement, once the largest low land sub-tropical rainforest in Australia. Today only remnants remain. Map in hand I drove through land once covered by this remarkable forest and could only feel sadness at man’s continual need to place economic considerations over our environment.

A week in the Richmond Valley visiting libraries, historical societies, driving extensively around the area and pouring over pastoral maps and reading early pastoralist and settler accounts and I’d decided on the location of English squatter, Mr Truby’s property as well as which portion of the now decimated Big Scrub my Irish cousins would have worked in, while the fictional river town in The Cedar Tree is loosely based on the historic river village of Coraki in the Richmond Valley, once a bustling river port.

You can’t write about the Irish in Australia in the 1860s without touching on the many accounts of anti-Irish sentiment. At the Lismore Historical Society I read stories of riots breaking out, eggs being thrown and, at the most petty level, Protestants and Catholics walking on opposite sides of town streets. Despite these differences NSW was changing. Those who had success in the timber industry or the goldfields, or who arrived as immigrants with coin in their pockets, were keen to settle on land. The NSW Robertson Land Act of 1861 was passed to break the squattocracy’s hold over vast tracts of land and open the country for selection and sale. Some squatters viewed this law as illegal and land disputes arose between the predominantly English and Scottish landowners and the would-be settlers, whether land speculators or honest settlers. Dummy agreements became widespread, with selectors picking the eye-teeth out of available land ensuring they had access to water – creeks and rivers, and using false names in order to buy holdings.

(Cedar-cutters. Image courtesy Byron Bay Historical Society)

It is into this period of turmoil in The Cedar Tree that Irish Catholic cousins Brandon and Sean arrive from County Tipperary. Brandon is eager to start a new life. Sean, unable to let go of the past. Their individual choices during their lives affect their descendants – none more so than Italian-raised Stella Moretti who goes against her family’s wishes and marries into the O’Riain family nearly a century later during World War Two. She unwittingly finds herself living on a sheep property on the barren edges of the Strzelecki Desert in Far West NSW, and slowly her life unravels.

Next week I’ll be sharing my desert experiences.

Hope you enjoy Cath – sorry for the delay in responding.