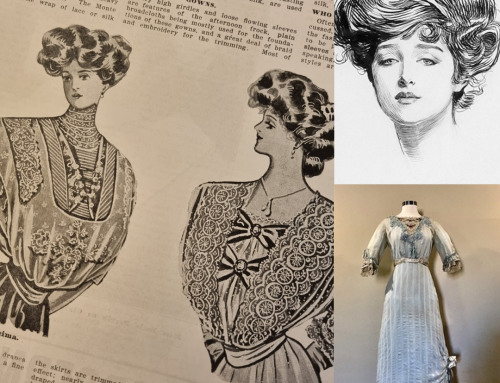

The river-boat era carries with it an inherently romantic history in Australian lore but like most industries it started through need. In 1851 Australia’s first gold rush took place at Ophir near Orange. Barely three years earlier gold had been discovered in California and now the mighty rush of humanity turned an eager eye towards New South Wales. The rush to the NSW field led to a serious decline in Victoria’s population and so a reward was offered to find gold in Victoria and stop the flow of people from the state. By the end of 1851 the Ballarat and Bendigo fields were in production and in 1852 100,000 prospectors arrived from overseas. Women and families were deserted, and crews abandoned ships. Between 1850 and 1860 Australia’s population more than doubled to over one million.

With this exodus to the fields the diversion of tools, timber and foodstuffs followed and with the demand for supplies teamsters and their drays were eager to fill the need. They turned away from their usual destinations such as inland towns and remote stations, to the more lucrative goldfields market charging high prices for the transport of goods. It soon became apparent that the inland with its wool and fledgling tin and copper mines and remote inhabitants in need of supplies would struggle without a viable alternative to transporting goods.

Savvy men turned to the Murray-Darling as a means of transporting goods and in the 1850s the river-trade was born with the Murray, Murrumbidgee and Darling Rivers becoming the new inland highways.

Generally, the Murray-Darling navigation season ran from June to February, depending on river heights, although the Darling season was shorter and less dependable, due to unreliable rainfall. Some three hundred paddle-steamers plied the Murray-Darling River during the main era of river trade, 1864-1914, offering a transport service for delicate and bulky cargo, mail and fresh food that greatly improved living standards and reduced isolation in remote areas.

The benefits were numerous. The price of food and goods fell for people living inland as they no longer had to rely on slow overland transport. And with the decrease in freight charges on wool, sheep production became more profitable. In turn more land was opened up for settlement. Industries such as sawmilling and ship building boomed and inland port towns sprang up with Bourke at one time the largest inland port for wool in the world.

But this invaluable service soon attracted the attention of the New South Wales government, with the river transport of wool from New South Wales to South Australian markets quickly becoming a matter of concern. Ensuring the proceeds from NSW-produced wool remained in the state became a primary objective. With that in mind, a railway from Sydney to Bourke was soon under construction and opened in 1885 with subsidised rail-freight offered to entice wool-producers from the river. Similarly, plans to construct more weirs and lochs to maintain river levels and trade on the Darling came to nothing. As more railway lines were built the river trade continued to dwindle. Unreliable rainfall, the 1895–1902 drought, and the Great War led to its inevitable end.

In the Last Station we meet Captain Ashby a paddle-steamer captain desperate to cling to the last vestiges of a dying world.

(Image: Paddle steamer Lancashire Lass pulling a barge with 1158 bales of wool at Wilcannia, NSW, c. 1905. Photo by G. Young, courtesy of State Library of NSW.)

Leave A Comment