I started writing a long time ago. I was in my teens when the bug first hit me. Poetry, short stories, news and travel articles. You name it. I wrote it. I was simply compelled to write even if I was exhausted after hours in my ‘day’ job, like most scribblers I couldn’t wait to sit down and put pen to paper. When my first novel was accepted for publication in 2008 and my agent rang to tell me the good news, I was so excited that I sat down on the cement floor in the middle of the cactus display in Bunnings Toowoomba QLD. Shocked, humbled, thrilled these were just some of the emotions I experienced. Although I’d been published internationally in various forms over the prior decades, the birth of a novel is something totally different.

It’s like WOW!

To me it was amazing that a publisher was prepared to take a risk and see if readers liked my work. Back then I gave little thought to the fact that they were able to publish me because there were available monies to be directed to newcomers such as myself. And where did that money come from? To be blunt, from the other novelists they published. From the big name, best-selling authors. From the profit margin. That’s what a healthy publishing industry does. But all that might change if Turnbull has his way.

Publishing and bookselling in Australia are subject to parallel importation rules. Basically this protects Australia from the dumping of cheaper books into our market. Currently, if an Australian publishing company owns the rights to publish any book in Australia, the Copyright Act stops other people, major booksellers, for example, from importing commercial quantities of that book from other markets. BUT, on Friday the Productivity Commission report on intellectual property recommended the government repeal parallel import restrictions for books to take effect no later than the end of 2017.

Thomas Keneally wrote in AFR Weekend that, “PIR represents the little ledge of copyright security, the small acre, on which we have created a respected publishing industry, one of the largest in the world, and a treasure house of writing of all kinds. On that said ledge, many successful books of Australian or international derivation enable the publication of more marginal Australian books and more risky ones that is the way a healthy publishing industry is run.”

That’s worth remembering, that the current system enables the publication of more marginal Australian books and more risky ones.

What literary gems, what sublime narratives, what brilliant minds may never see the light of day.

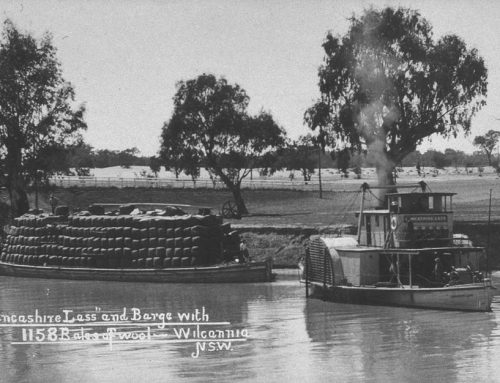

And what about our cultural heritage. Our literary canon.

Keneally goes on to say that, “It is worth saying that PIR does not restrict individual readers from buying books from anywhere in the world, and book retailers can order single copies from anywhere in the world on behalf of a customer. ”

Australian publishing produces more than 7000 books annually and supports over 1000 related businesses. Daniel Munoz

Australian publishing produces more than 7000 books annually and supports over 1000 related businesses. Daniel Munoz

A report by Systems Knowledge Concepts stated “Without parallel import restrictions, Australian publishers would be exposed to all the risks and failures but be unable to benefit from the successes.”

Consider what happened in New Zealand when they canned the PIR legislation in 1998. Since 2008, according to Nielsen Bookscan, the range of books published there has shrunk by more than a third, and sales are down 16 per cent. The cost of their books have gone up.

Leave A Comment