What a task I set myself in the reviewing of Atonement, Ian McEwans Booker prize winning novel of 2001 and a work which was listed as one of the top 100 reads of all time by Time Magazine. Atonement is part love story, part war story and also a story about stories.

The first half of the work is set at the Tallis home in the English countryside in 1935. A childish thirteen year old, Briony Tallis is preparing a play to welcome home her brother, Leon. The Tallis home gradually fills with Cecilia – Brionys older sister, a wealthy industrialist, Paul Marshall, Leon and cousins whose parents have split, nine year old twin boys and fifteen year old, Lola. We also have a Mr and Mrs Tallis, the first always absent due to a London based job, the second, a physically weak woman. Robbie Turner, the housekeepers son and the beneficiary of a first rate education thanks to Mr Talliss largess also appears.

The first half of the work is set at the Tallis home in the English countryside in 1935. A childish thirteen year old, Briony Tallis is preparing a play to welcome home her brother, Leon. The Tallis home gradually fills with Cecilia – Brionys older sister, a wealthy industrialist, Paul Marshall, Leon and cousins whose parents have split, nine year old twin boys and fifteen year old, Lola. We also have a Mr and Mrs Tallis, the first always absent due to a London based job, the second, a physically weak woman. Robbie Turner, the housekeepers son and the beneficiary of a first rate education thanks to Mr Talliss largess also appears.

Throughout this first part there is a sense that something is going to happen. Conversations are overheard, things are seen: Robbie writes two letters to Cecilia and has Briony mistakenly deliver the wrong one, Briony witnesses a moment of sexual tension between Cecilia and Robbie, later she finds then making love in the library which leads her to decide he is a maniac.

When the twins run away during dinner and teams are sent out to search for them, Briony sees cousin Lola attacked by a stranger on the grounds. With Lola unsure of her predator, Briony decides it must be the maniac, Robbie.

Brionys betrayal ruins two lives, however the true criminal is never caught. Its interesting in that the true identity of Lolas attacker is pretty obvious, yet the reader becomes intrigued with how Briony will react. Tragically her betrayal of Robbie to the police is shockingly awful, with her act compounded by the rest of the Tallis family who are quick to believe Briony. Everyone that is, except Cecilia. Brionys accusation comes right in the middle of the novel and although the build-up has been long, its definately worth the wait.

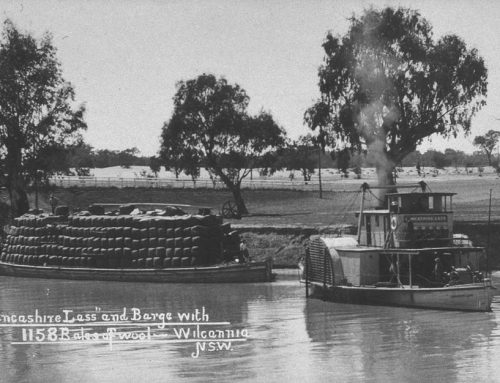

Here McEwan emphasises the class society of England. Although Robbie has been educated at Cambridge, has grown up with the Tallis children and on the night of his arrest has been dining at the Tallis home, he will forever be the housekeepers son. The Tallis family close ranks.

From this point, the second part of the novel jumps to the Second World War. Robbie is in France fighting. Cecilia, having cut- off all ties with her family, except for Robbies mother is a nurse, and Briony is studying to become a nurse in war-torn London. We spend some time with Robbie in France, albeit anxiously waiting to discover what happened in the intervening years. He is desperate to get home to Cecilia. Her signature ending to her many letters to him at the front, Come back to me, becomes a haunting backstory to the remainder of the novel. Will they see each other again?

Robbie has spent a number of years in gaol before being sent off to war and Cecilia has only seen him only once for thirty minutes since Brionys betrayal. Once gain this technique builds the tension of the novel.

We switch back to Briony who has gone from teenage playwright to would-be novelist. It becomes obvious that Briony has been submitting to publishers what in fact will eventually become the novel Atonement. This is interesting as shes not necessarily desperate to be forgiven by those shes wronged-a realisation of her crime has arrived gradually with age – rather, her personal atonement is actually writing about it. That is, putting her crime on paper for the world to read. The problem of course is that she must wait until everyone associated with the story is dead. Does she have concerns regarding libel? Or rather is she the coward that McEwan occasionally hints at.

The last section of the novel is set in London in 1999. The now famous author, Briony is dying and, Atonement, the novel, has finally been published. Briony has used fiction to ensure her real-life characters receive the happy ending they deserved and which both her betrayal and the war took from Cecilia and Robbie.

McEwan makes a polite stab at contemporary fiction while reminding us of what it means to craft a story. As always the author decides what happens in the story, leaving us with what is the truth of the story, and for me at least, what is wishful thinking.

What sense or hope or satisfaction could a reader draw from such an account? Who would want to believe that they never met again, never fulfilled their love?

For me I felt robbed of a dramatic, if not brutal ending. I never have been a reader desperate for a happy ending. I prefer to be enthralled and entertained, yet McEwans jump to 1999 was executed so beautifully it brought a gasp to my lips, both for its craftsmanship and final revelations.

Leave A Comment