On the 3rd March 1885 an infantry and artillery battalion of 758 men and officers set sail from Sydney for the Sudan with great fanfare. By the end of the month they had reached their destination. It was an important milestone, for never before had an Australian colony sent paid soldiers to fight in an Imperial War. NSW made the offer of men to the British following the news that General Charles Gordon had been killed in the Sudan. Gordon had been attempting to thwart an indigenous rebellion against the British-backed Egyptian regime in the country, but like most leaders he took matters into his own hands. Specifically sent to oversee the extraction of Egyptian survivors after their attempts to crush the revolt failed, instead Gordon decided to end the rebellion. However, he too was unsuccessful, finding himself and his men besieged in Khartoum. A rescue party was sent but that expeditionary force was still fighting along the Nile when Gordon was killed in January 1885.

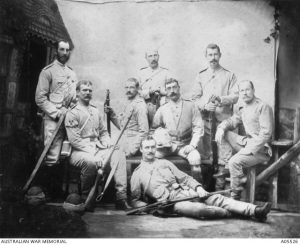

(Image-courtesy AWM. Sydney, NSW, 1885: infantrymen of the NSW Contingent to the Sudan, after their return to Australia. They are wearing khaki uniform issued for active service, and are equipped with Martini-Henry rifles.)

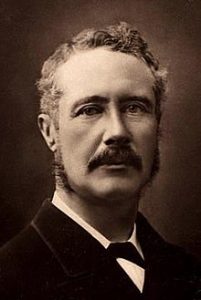

You might be wondering how a British general killed in a distant state in North Africa in the 1880s could lead to the colony of NSW offering soldiers for the cause. But the simple truth was that General Charles Gordon was a hero to many British subjects and his death was considered appalling. Gordon, a British Army officer fought in the Crimean war and was Governor-General of Sudan in the late 1870s until 1880 when he resigned due to exhaustion, but not before he had ended a number of revolts and tried to decrease the local slave trade. However, it was his command of the ‘Ever Victorious Army’ in China, during the 1860s leading Chinese soldiers that his military reputation was made. Gordon and his men were credited with putting down the Taiping Rebellion and he received honours from the Emperor of China and the British. ‘Chinese Gordon’, was a legend.

While our men left Sydney with great enthusiasm, they saw only limited skirmishes. Most spent their time attending to boring guard duties and worked on a desert railway being laid in the direction of Berber on the Nile, part-way between Suakin and Khartoum. Australian casualties were few and those that died mainly did so from disease. Back at home the working-class were against participation in the war. People voted against a patriotic fund and the Nationalist Bulletin magazine wasted no time in mocking the contingent, before during and after the men’s return. But many Australians thought our engagement an important step in the development of the colony and for those living on remote properties the battles of the Sudan were cut from Illustrated Magazines and plastered to walls in place of wallpaper, an ongoing monument to the greatness of the British and NSW’s involvement despite Gordon’s defeat.

(Major General Charles Gordon)

(Major General Charles Gordon)

Leave A Comment