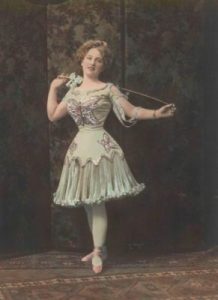

Australia’s first circus opened in Launceston, Tasmania in 1847. Three evenings a week, in the yard of Radford’s Horse & Jockey Inn, Robert Radford’s company presented feats of horsemanship, dancing, vaulting, gymnastics, acrobatics and clowning. Circus-like exhibitions had been given previously, however no-one had ever seen anything quite like this before.

Australia’s first circus opened in Launceston, Tasmania in 1847. Three evenings a week, in the yard of Radford’s Horse & Jockey Inn, Robert Radford’s company presented feats of horsemanship, dancing, vaulting, gymnastics, acrobatics and clowning. Circus-like exhibitions had been given previously, however no-one had ever seen anything quite like this before.

This circus launched the careers of major circus performers and owners, including Golding Ashton, later known as ‘James Henry’ Ashton. A founding father of one of the great Australian circus families, it was Ashton who took to the bush. Having sailed from Tasmania so that his troupe could perform in Melbourne in 1849, they were refused the right to perform by authorities worried that the event may disrupt the public and cause mischief.

Ashton wasn’t going to be beaten. With the help of an Aboriginal tracker he led his troupe through the bush carrying all their possessions by packhorse. Eventually they reached Sydney and it was here that they gave equestrian exhibitions in a makeshift ring near present-day Central Station.

The popularity of circuses grew quickly. These travelling shows reached distant towns, remote shearing sheds and mining camps. In a time when entertainment options were non-existent in some places and many couldn’t read, the circus was a great boon. Early circuses supported the bush. They helped with the construction of vital services such as schools and hospitals and even our bushrangers usually waved traveling circuses on. Such was the case with Thunderbolt and the Wirth Brothers. I used the Wirth Bros circus as a basis for my research for An Uncommon Woman, and could easily understand how popular these shows were in the outback. This was entertainment. A major spectacle. It was a chance to go to town. To see friends. To be among the company of many. To have a chop-picnic (roasted meat – the term barbeque came later) and maybe some peanuts in a paper cone.

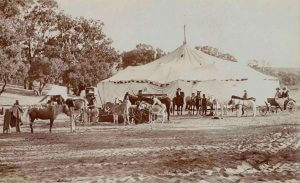

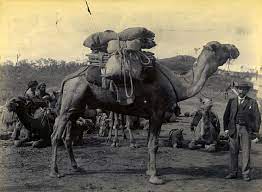

I was staggered by the amount of work that went into a circus travelling through the bush. Forward riders were sent out to hang posters in towns announcing their imminent arrival. Fodder had to be sourced for the ‘hay-eaters’, meat for the big cats and water had to be plentiful. By Federation in 1901, all States except Western Australia were ‘linked’ by rail and more than 20,000 km of track had been laid. It was a mammoth effort to load and unload the circus wagons. To set up the big top, display the animals in a pre-circus petting zoo, parade down the main street with a band to entice spectators, to ensure there were good ticket sales. By the early 1900s, one of the most financially rewarding show routes ran almost the entire length of Australia’s eastern seaboard, from Bega on the south coast of New South Wales as far as Cairns, on the coast of far north Queensland.

I was staggered by the amount of work that went into a circus travelling through the bush. Forward riders were sent out to hang posters in towns announcing their imminent arrival. Fodder had to be sourced for the ‘hay-eaters’, meat for the big cats and water had to be plentiful. By Federation in 1901, all States except Western Australia were ‘linked’ by rail and more than 20,000 km of track had been laid. It was a mammoth effort to load and unload the circus wagons. To set up the big top, display the animals in a pre-circus petting zoo, parade down the main street with a band to entice spectators, to ensure there were good ticket sales. By the early 1900s, one of the most financially rewarding show routes ran almost the entire length of Australia’s eastern seaboard, from Bega on the south coast of New South Wales as far as Cairns, on the coast of far north Queensland.

The golden age of the circus lasted from the 1850s until the early 1960s. But by the 1920s the circuses were already feeling the competition from the advent of the gramophone and the talkies (movies). The days of touring abroad were fast disappearing. It was the bush that kept the industry alive. And the travelling show business provided livelihoods for thousands of show people – entrepreneurs, performers, other employees, as well as freeloaders and dreamers, hopeful of seeing the world. It was the entertainment of the day and it wasn’t difficult imaging the excitement that a circus brought to the bush.

In the 1950s when the circus came to Moree, my father travelled the 116 kilometres from the property to attend with friends. He fell in love with a lion cub and offered the keeper fifty pounds for it, all the money he had with him at the time. The lion keeper refused, saying he couldn’t take anything less than one hundred pounds. Dad missed out on the baby lion, however years later he told me that he’d had this vision of a lion cub laying by his feet in the homestead dining-room. Probably not the best of ideas considering we were a sheep stud in the 50s. And so another family story led to an idea in a novel.

Leave A Comment