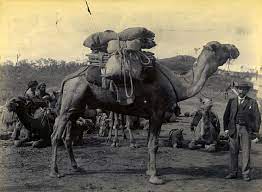

From the 1860s to the 1930s Afghan cameleers were indispensable in servicing Australia’s inland pastoral regions. Although known generically as Afghans these expert teamsters came from the North-West frontier province (then under British rule) now known as Pakistan as well as Iran, India, Afghanistan, Egypt and Turkey.

‘Harry’ the first camel to arrive in Australia disembarked at Port Adelaide in 1840 and was used in an 1846 expedition by John Horrocks. ‘Harry’ the camel became widely known but met an untimely end when blamed for Horrocks’ death and was later put down. This unlucky start only briefly slowed the arrival and gradual spread of camels and their teamsters. Initially small groups of cameleers were bought into Australia by ship on a three-year rotational basis, however by 1860 people were beginning to see the benefit of camels in Australia’s arid interior. They were used in Burke and Wills’ expeditions and six years later more than 100 camels were imported. During that same decade around 3,000 camel drivers came to Australia from Afghanistan and the Indian sub-continent, along with more camels. The age of the cameleer had arrived.

The majority of cameleers, including Indian cameleers, were Muslim, while a sizeable minority were Sikhs from the Punjab region. They quickly became established and set up camel-breeding stations and rest-house outposts, known as caravanserai, throughout inland Australia. These rest-stops created permanent travelling routes between coastal cities and the remote cattle and sheep grazing stations, ensuring the vital transport of goods, mail and wool but also playing an important role in exploration, communication and settlement.

While many cameleers eventually returned to their homelands, some stayed in Australia and married local Indigenous and European women in outback Australia adding to our rich tapestry of cultures. The ‘ghans’ as they came to be known, either lived on stations or on the edges of white settlements in ‘ghantowns’. The ‘ghantown’ at Bourke has long since faded but you can visit the Bourke cemetery where several cameleers are interred and view the corrugated iron mosque that was moved from the original ghantown site.

While settlers appreciated the cameleers help the ‘ghans’ were never truly accepted. They were ostracised for their appearance and religion and even the wealthiest educated Afghans were never truly acknowledged. In Bourke there are accounts of cameleers being thrown off the Bourke bridge and into the Darling River. Competition was rife, with white teamsters angry at the ‘ghans’ taking their trade, a situation not helped by the various state laws that curtailed Afghans from the rights of normal citizenship culminating in the Immigration Restriction Act of 1901 which refused Afghan’s entry into Australia when returning from visits home to see family.

And yet during the Federation drought of 1995-1902 when there was little navigational water in the western river systems of NSW the cameleer’s assistance in transporting goods saved some inland towns from oblivion.

This research was undertaken for Nicole’s latest novel: The Last Station

(Image courtesy: Main – Camel trains. The Royal Queensland Historical Society. 2. Grave of Afghan cameleer Zeriph Khan (1871-1903) at Bourke Cemetery, NSW – Authors collection)

Leave A Comment