The world’s most beautiful war memorial spans 243 kms and was built by men who served during the Great War. The Great Ocean Road was first planned towards the end of World War I, when the chairman of the Victorian Country Roads Board asked the State War Council for monetary assistance. The funds would enable returned soldiers to build roads on the south-west coast of Victoria an area that for many was only accessible by sea or rough bush tracks. The works would help isolated communities connect with each other. However, it was with trepidation that the first field party of surveyors entered the area. They were confronted with dense scrub with their progress so slow that they barely averaged three kilometres a month.

The 3,000 servicemen recruited to build the new road were keen to be involved. This was to be a war memorial for those men who had not returned from the war, a lasting monument to their fallen brothers-in-arms. However the difficulties of clearing a path for the road and then building it in such arduous terrain must have made some of the hardiest workers wonder if the project would ever be completed. Construction was done by hand. Although some small machinery was used, picks and wheelbarrows were the main equipment, along with explosives. Several workers were killed on the job.

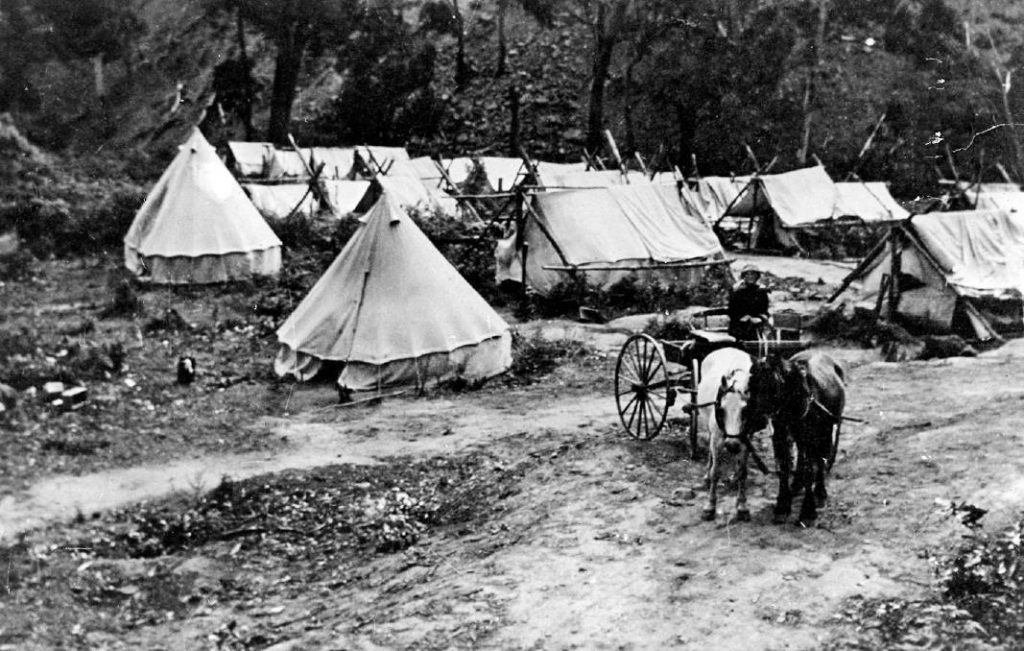

(Camp site Great Ocean Road. Image courtesy Wikipedia – not attributed)

When the road was finally finished and opened in 1932 it was a challenging drive, full of twists and turns, with sheer drops and patches of dense forest, in many places only suitable for one car at a time. Today the Great Ocean Road starts at Torquay and travels 243 kilometres westward to finish at Allansford near Warrnambool, along the way it covers some extraordinary coastline and scenery, including limestone and sandstone cliffs, beaches, rainforests, the Shipwreck Coast and of course, the The Twelve Apostles. For those of us fortunate to drive along its bitumen surface and admire the view along the way, spare a thought for the returned soldiers who carved a path through the area, camping in tents and sometimes risking their lives and earning 10 shillings and sixpence for eight hours a day.

Leave A Comment