It was pretty tough being a settler in Australia in the 1830s and tougher still for the First Australians. Imagine you’re a white settler and have just arrived in the colony of New South Wales after five months on-board a sailing ship en route from the Mother Country – England. On arrival you discover that the fertile farming land you hoped to settle doesn’t exist anymore. It has already been granted, leased or sold to those who have come before you: free settlers, assisted emigrants, emancipated convicts and members of the military among others. To make matters worse, the great Australian Agricultural Company formed in England with the input of Governor Macquarie has recently been granted over 560,000 acres of farmland stretching from present day Murrurundi in the Hunter Valley to Tamworth. This massive grant does two things. It displaces many illegal settlers who are forced to find farmland elsewhere and secondly it takes away arable farmland from the northern fringe of the colony that could have been made available to newcomers.

You consider your options and realise that you have little choice. You must go beyond the outer limits, outside the designated nineteen counties of the NSW colony. Far from the jurisdiction of the law to the white space on a map, the wild lands of Northern NSW. You travel northwards, taking all your worldly possessions with you, over-landing sheep and carrying provisions by bullock wagon. The provisions are your life blood. You’ve spent your savings buying livestock, equipment and food, but anything could happen during the journey. You could simply get lost. One of your party may fall ill. God-forbid you’re attacked by the indigenous inhabitants, your stock speared or rushed off into the scrub. Your food stolen. Your wagon bogged or overturn. If and when you do make it through to untouched land you then have to mark the farm’s boundaries by blazing trees with an axe and the problems you had travelling northwards don’t disappear, in fact they’re compounded because now you have to establish your business, grow food to survive, before your provisions run out.

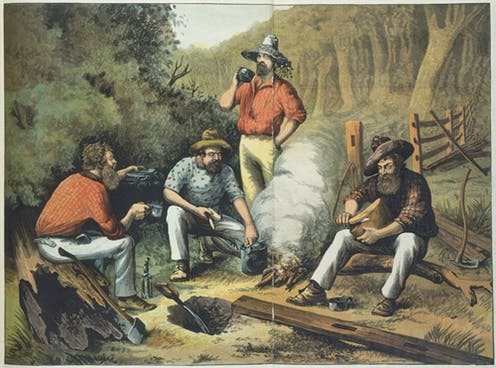

(Image courtesy- Tea and Damper by A . M. Ebsworth. Digital Collection – State Library of Victoria.)

You live on mutton and kangaroo meat. On damper, sugar and water feeling the growing effects of scurvy. You wear a brace of pistols and carry a flintlock musket while you ride around your run and at night you stare at a too big sky, at foreign stars, at a moon so large that you wonder whether the stories of moon madness are true. You sleep with a pistol by your side, stare at your wife and child. You shouldn’t have brought them out here to this god-forsaken land, but you had no choice. This is supposed to be a fresh start in a new world but you don’t know if you will survive, let alone succeed and with every move you make you feel as if the bush is watching and waiting. All of you are afraid.

The Aboriginals don’t want you here. They don’t want their country invaded. They don’t want their ancient traditions altered. They don’t want you here on land that they have protected and nurtured for thousands of years. You try and befriend them. You try and be fair. To understand their ways. To co-exist. And you have some success. But other settlers don’t think the way you do. A law has been passed. Terra nullius. It states that no-one owned this land before the British Crown took possession of it.

You graze the land not realising that your sheep are fouling the waterways, trampling the fragile grasses, scaring away the wild animals the Aboriginals hunt for food. You don’t believe that they burn the land to entice new growth, and wildlife, for food, to control timber and in doing so reduce the risk of bush fire. That this is why the country looked so magnificent on your arrival. Much like English parkland. The grasses reaching to the stirrup-irons on your horse.

(Image – Botany Bay NSW. Undated – Trove)

The attacks soon begin. Aboriginals are killed. Shepherds are speared. Stock are rushed off into the scrub. The settlers grow more anxious and call on the Governor for help but he tells them they have settled beyond the reach of the law. That they are on their own. The settlers, along with assigned convicts and emancipated stockmen decide to take matters into their own hands. And that’s when the real troubles begin.

Footnote:

(The Myall Creek massacre occurred in 1838. It involved the brutal killing of at least twenty-eight unarmed Indigenous Australians by eleven colonists at Myall Creek near Bingara, in northern New South Wales. It was one of many frontier conflicts that took place between Indigenous Australians and white settlers during the British colonisation of Australia. The first fighting occurred several months after the landing of the First Fleet in 1788 and the last clashes occurred in the early 20th century, as late as 1934. A minimum of 40,000 Indigenous Australians and between 2,000 and 2,500 settlers are estimated to have died in these conflicts)

Leave A Comment