Our first agricultural college was established in 1883 at Roseworthy in South Australia. Gradually, other farm schools sprung up across the country, with women admitted to some during World War I to develop farming skills while the men were away at war. However not everyone received the training required when it came to learning how to work the land.

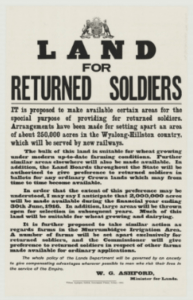

Soldier Settlers were often one such group. The soldier settler plan was begun during The Great War, with South Australia enacting legislation in 1915. It seemed like a grand plan to look after our returning soldiers and their families by way of granting land to selected veterans. Similar schemes gained momentum across Australia the following year following a report prepared by the Federal Parliamentary War Committee.

On paper, the idea undoubtedly looked promising. In most cases, Crown land was set apart for returning soldiers. Although some privately owned land was also resumed for the project. In order to buy or lease such a block returning veterans had to remain in residence on that land for 5 years. Apart from providing homes and work for returning soldier’s and their families, it was seen as a reward of sorts at a time when employment opportunities were becoming scarce. But the government had a bigger agenda. They also hoped for a population expansion, an increase in commodity production and infrastructure, and they would do it by allotting land, in some cases, in our remoter rural regions.

On paper, the idea undoubtedly looked promising. In most cases, Crown land was set apart for returning soldiers. Although some privately owned land was also resumed for the project. In order to buy or lease such a block returning veterans had to remain in residence on that land for 5 years. Apart from providing homes and work for returning soldier’s and their families, it was seen as a reward of sorts at a time when employment opportunities were becoming scarce. But the government had a bigger agenda. They also hoped for a population expansion, an increase in commodity production and infrastructure, and they would do it by allotting land, in some cases, in our remoter rural regions.

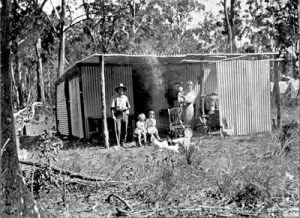

Soldiers who were successful in receiving a block of land could try their hand at a number of activities such as wool, dairy, cattle, pigs and fruit. But the allotment program didn’t work for everyone. Some of the land was located in remote areas, required substantial clearing and were barely large enough to eke out a subsistence living. In these cases, men with little money found themselves quickly indebted to the government with the borrowing of funds required to make their new holdings productive or to simply put food on the table.

There was also a lack of education. For urban based men, the opportunity of land must have seemed a gift from the heavens, however not everyone knew what they were doing. In closer settled areas, such as Glen Innes in NSW, a coordinator was appointed to check on the progress of each settler. One such man, according to my grandfather (who told my father), rode around the properties on a bicycle, traversing hundreds of miles in an effort to check on new farm owners and advising them. New farmers, having decided on a chosen commodity, often then had to build their own homes from local material sourced on the property and relied on settler pamphlets when constructing stables and yards. For many the settler coordinator was a life-line.

When I first heard of this I was reminded of the research I’d done for my novel, Wild Lands. Settlers heading off towards the white spaces on a map in the 1700s and 1800s with all their possessions on a wagon and a settler booklet tucked securely away with instructions on how to build a home and grow a crop.

Not many settlers knew what they were signing up for all those years ago and not every new soldier farmer knew what they were doing when it came to making a living from the land following the First World War. Stories of the settler coordinator returning six months later to check on his charges underline the problems with the soldier settler program. Anecdotal evidence suggested that one new owner had erected a pig-sty instead of stables. Another had purchased beef cattle instead of dairy. Crops failed. Some walked away. Families were split. Had more funds been available to ensure a coordinator could visit some of these properties more frequently, many of these problems may not have occurred.

Not many settlers knew what they were signing up for all those years ago and not every new soldier farmer knew what they were doing when it came to making a living from the land following the First World War. Stories of the settler coordinator returning six months later to check on his charges underline the problems with the soldier settler program. Anecdotal evidence suggested that one new owner had erected a pig-sty instead of stables. Another had purchased beef cattle instead of dairy. Crops failed. Some walked away. Families were split. Had more funds been available to ensure a coordinator could visit some of these properties more frequently, many of these problems may not have occurred.

These initial land allotments resulted in triumph for some and despair for others. After World War I, some of these new farmers, unable to cope with our severe climate changes and devoid of the capital to increase stock or quality of life, simply walked off the land back to the large towns and cities from whence they had come. Many more spent years tramping around the outback looking for work.

In An Uncommon Woman the character Will is the son of a returned soldier, a veteran of the Great War. Will’s father is the recipient of a soldier settler block, but the family are unable to make a go of it. The soldier settler story of Australia moulds Will’s character in An Uncommon Woman. He is a young man troubled by his families past. Embittered by the struggle of life but keen to better himself. Writing our pastoral history in fictionalized terms is an honour, but in the process you also learn of the many hardships endured in the formation of this great land.

WA, so true, success and failure by the acre back then..