If you close your eyes you can see them resting during a break in the fighting on one of the Somme battlefields. The trench is cold and clammy, the men, quiet. Some sit on upturned wooden crates, others crouch low, their backs chilled yet sweating against the earthen wall. Filthy fingers hold hand-rolled cigarettes, lungs drag heavily on coarse tobacco. They’ve just been given word that a rum ration is to be issued. That means they’ll be going over the top again. One digger has a shrapnel wound on his leg, a filthy field dressing covers the blood soaked woollen material of his uniform. Occasionally he looks at it with annoyance.

His mate props his tin hat further back on his head, licks the stub of his pencil and jots a few more lines home. It’s hard to know what to write. He sniffs, wiping his nose along the arm of his tunic. The smell of cordite fills the air, to the right of him in the distance, explosives boom out, German shells. He concentrates on the earth walls of the trench and on the stink of wet sandbags. Suddenly a shell hurtles overhead, exploding with a thudding roar. Clods of earth shower down on the men as they crouch low and tight against the trench wall. A sprinkling of white dust, chalk deposits blown up from among the rich brown soil of the French countryside falls like ash, then there is a scream and the all too familiar call for stretcher bearers.

The German invasion of France in August 1914 saw millions of soldiers digging two lines of zig-zagging trenches that stretched for five hundred miles across Europe, from the North Sea to Switzerland. These trenches would remain virtually unchanged until the war ended four years later. The area between the opposing forces was known as ‘No Man’s Land’, a continually deteriorating sea of mud, filled with shell holes, sandbags, barbed wire, corrugated iron and the dead. This was the Western Front or what became commonly known as the Somme battlefields, named after the region and the river Somme. The Germans were forced to fight on two fronts: on the Eastern Front they battled Russia, on the Western they fought against France, Britain and countries of the British Empire, such as Australia and eventually the United States.

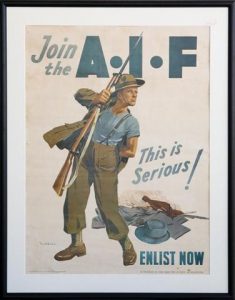

The Australian Imperial Force (AIF) first came to France in March of 1916, following retraining and reinforcement in Egypt after the Gallipoli evacuation. By the time the AIF arrived on the Western Front about half of its members were Gallipoli veterans and half were new recruits.

Most thought this war would be an adventure, even the Gallipoli veterans believed nothing could be worse than what they had already endured and as the transport trains rolled through the lush French countryside many felt excited, keen to see a bit of action. Then the landscape began to change. The countryside became scarred. In many cases it resembled a moonscape with blasted soil, huge gaping craters and endless open country devoid of trees, all caused by heavy artillery.

The First World War was on a scale previously unknown and in a period of unprecedented innovation. During four brief years, three major new weapons were introduced-gas, tanks and aircraft. Machine guns and modern quick artillery were well established, but the new science of using the big guns, such as greater distance and targeting ability increased their effectiveness a thousand fold.

(The AIF, Egypt – Image courtesy of the Australian War Memorial)

Where war had once been a matter of attacking and defending, like the great troop and cavalry charges of the 1800’s, troops quickly discovered that leaving the trench, going ‘over the top’ was suicide. But that was exactly what they were forced to do. As one side staggered through the mud, snow or slush towards the enemy lines they would fall into slimy shell holes, suffer a gas attack, trip over the dead and dying and invariably become entangled in coils of barb wire only to be mowed down in rows by enemy machine guns. It was not uncommon to lose two or three thousand Australian’s over a kilometre wide front in a single engagement that may have lasted six or seven hours.

After three years of fighting in which both the German and allied trench systems remained virtually unchanged, the year 1918 began with the Germans launching their Spring Offensive in March. Buoyed by an additional 50,000 troops from the Eastern Front, following Russia’s surrender, they anticipated victory. If they could break through the Allied lines there was a possibility that they could reach the French coast and reopen supply lines blocked by the British navy. If they failed they would lose the war. And they had little time, for America’s huge army was finally ready to join in.

Led by crack assault troops the Germans advanced, breaking through British lines at several points and sweeping across former battlefields that the Allies had taken months to capture at great loss of life. On the 4th of April 1918, the Germans attacked Villers-Bretonneux in strength. This small village lay 16 kilometres east of Amiens, an important rail junction which if captured would give the Germans’ a clear run to the coast.

Troops who were part of the 5 Australian Divisions were urgently brought by rail from Belgium to prevent a German break-through. On this day ninety years ago, charged with recapturing Villers-Bretonneux and blocking the German advance to Amiens, the Australians fought through the town, street by street, cellar by cellar, driving out the Germans as they went. Using grenades and bayonets they stormed through a hail of German machine guns, many knowingly going to their deaths. Their capture of the Village of Villers-Bretonneux and the surrounding key terrain, was the battle that not only stopped the German advance but also forced the Germans to withdraw.

General G.W. St. G. Grogan, himself the recipient of numerous awards for valour called the Australian attack on Villers-Bretonneaux,

‘Perhaps the greatest individual feat of the war.’

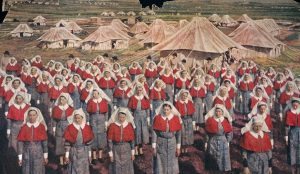

(Nurses of the 2/5th AGH on parade in Palestine, awaiting inspection by their matron. Image courtesy Australia in the Great War)

Our Australian forces earned a reputation as fierce adversaries and welcomed allies in places such as Pozieres, Fromelles, Mont St Quentin and countless other sites, yet it is significant that in spite of some of the fiercest fighting in history in these places, that the major Australian War Memorial is at Villers-Brettonneux. In memory of this battle and in recognition of 2008 being the ninethieth anniversary of the end of World War I, the very first dawn service was held at Villers-Brettonneux in France.

In order to understand the esteem in which Australian’s are held in rural France and specifically Villers-Brettonneux, one only has to visit this French village. Here their main street is called Rue de Melbourne, the town symbol is a kangaroo, the local basketball team are Les Dingos and the children sing Waltzing Matilda and play in a koala club. At the primary school where children dash across the play ground to shake hands with visitors there is a large sign on the school building, ‘Do not forget Australia.’

More than 330,000 Australians served in the First World War, 60,000 of them were casualties, 8,000 at Gallipoli. There were 52,000 casualties on the Western Front. Today these men and women lie in 523 cemeteries across France and Belgium.

The Australian War historian, Charles Bean said,

‘What these men did nothing can alter now. It rises as it will always rise above the mist of ages, a monument to great-hearted men and, for their nation, a possession forever.’

This is beautifully written. Thank you. I attended the dawn service in wagga this morning but at not point did any dignatory or defence personnel stand up and give an address about what Anzac Day means- suffice to say I left the service feeling the day was a little incomplete. On coming home and cooking my eggs on toast breaky, I scrolled through Facebook and saw your post and it made my Anzac Day to reflect on the true scale of sacrifice and suffering that our troops endured. I particularly loved reading about the small village in France which commemorates our aussies in everyday ways.

So thank you for completing my Anzac day and reminding me why I get a shiver every time I hear the last post.

Lest we forget.

Hi Katie

thanks for contacting me. My paternal grandfather fought during the Great War but even if he had not, I would have written the same piece. I march most years and like you, am always hopeful of an inspiring speaker on the day. Someone who can conjure the past and speak of the spirit that is Anzac

N.