Today, Ian Park visits. Some of you may have already read A Youth Not Wasted, his highly enjoyable memoir-cum-autobiography of his outback experiences as a young man. I’ve already previously profiled the book, however in speaking with Ian some months ago I really wanted to hear from him personally and he graciously agreed. In reading A Youth Not Wasted I could see similarities not only between both my father and grandfather’s generations, but also in my own experiences in the bush. It’s a fascinating read for those of you who may be more urban based and a reminder for those of us in more regional and rural areas of how this great land, Australia was forged. Enjoy.

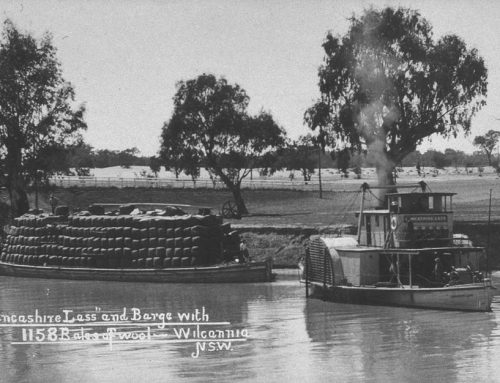

A Youth Not Wasted is about the halcyon years of outback sheep stations, when the owners of vast properties had special status in Australian society and their stations were like feudal empires. Wool prices were at their peak. Wool was Australias biggest agricultural export and it seemed to be a world without end. My mothers father was a sheep station manager, as was her brother. So, although I was born in Perth and went to school in the city, I grew up in a family culture that was firmly connected to the bush. How could I resist the lure?

In January 1951, at the age of sixteen, my family sent me to a merino stud in Burra, South Australia. From there I was sent to work on another property further north. But home was in Western Australia and I returned to work on iconic stations like Mount Augustus and Belele.

In mid 1955 I contracted an illness called pericarditis, which put me in hospital for three months. That gave me the leisure to read and to talk about what I was reading. I was a reader from my earliest boyhood years and that continued while I was in the bush. Because I thought my youth was so memorable I was burning to write about it and I started scribbling as soon as I was out of hospital. At that time, I did not know that the way of life on outback sheep stations, that Id enjoyed so much, was coming to end and it is now gone.

Although I have had a successful business career and have a family in the city, the outback is still in my blood. I miss the country of the Murchison and the Gascoyne. I miss the silence and the solitude. I miss knowing there is not another human being within 50 kilometres. But I no longer want to live permanently in that environment. The answer, of course, is to revisit old haunts and I do.

An especially formative time for me was when I was alone in the bush for two weeks, repairing a fence. I had just turned 19. The homestead was 30 kilometres away, across very rugged country with a barely discernible track. It was high summer. These were long hard days, redeemed by peaceful, restoring nights.

I also enjoyed being self reliant and, knowing that I can be, has enabled me to deal with the many challenges that life and business throw up.

Only in recent years have I had the time to write about my youth. That vital, colourful way of life that was once quintessentially Australian is over and my book is a record for posterity. It is also my gift to my four daughters, so they can see how their father thought and felt as a young man.

As testimony to its authenticity, I am delighted that one reader who spent 60 years in the bush said, Its about my life. Another said, Thats exactly the way it was.

Leave A Comment