The Heart of A story: Characters & Conflict.

Why are characters so important in writing, because they literally pull the reader through the book. Thats why its so vital to have a compelling main character. When I think of memorable characters Scarlett OHara comes immediately to mind.

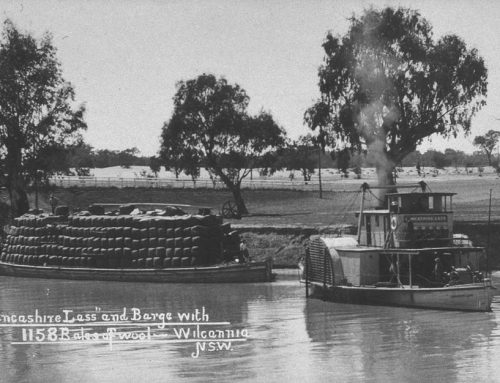

There is a reason why Gone With The Wind remains the top selling novel of all time. Scarlett is a gutsy, beautiful, conniving heroine and the equally scandalous yet debonair Rhett Butler is a marvellous foil to her wilful ways. Add a tumultuous period in history and a love story for the ages (forget Rhett, the story is actually about Scarletts love for the land-one of the many themes in the work is ownership) and the ingredients so carefully woven together in the narrative compel the reader onwards.

As a rule characters should not be predictable, unless the storyline calls for it. Depending on the work they can be stylised and the whole point of the story with very little setting detail; however most characters fall into the lifelike category. They are human after all and as humans they are multi-faceted; at times endearing, at others frustratingly annoying. As a writer I like to know my characters inside out, particularly my main character/s. I call this CSI profiling a method I started using a good eighteen years ago in the creation of my short stories. In building a character I construct an entire life around them. My characters have extended families, genetic predispositions (both physically and in terms of personality) and they have strengths and weaknesses. They may love Blues music, go on gut reaction, have poor posture or a habit of invading anothers personal space when in conversation.

As I mentioned in last weeks blog I start preparing for a new work by visualising my characters and drawing the story in my mind. It is only after theyve been with me for a while that I start my CSI file and this file is added too as I write. Of course much of this information may not be used in the final work, however it does certainly assist in the creation of well-rounded characters and if youre 50,000 words into a 140,000 word novel, with numerous sub-plots and minor players, a character file can work wonders for continuity. Its a little like watching a movie and noticing a change in lipstick colour or an item of clothing in the same scene. It throws the viewer back into reality, a jarring effect that does the complete opposite of what the creator intended. The storytellers ultimate aim is to suspend reality and immerse their audience in new worlds, no matter the genre. An abrupt change in a personality trait (unless were talking a serial killer) or perhaps a limp that swaps limbs can break the flow of a great story.

Once you know your character inside out, construct a character checklist, you could begin with the following:

- What does your character want more than anything in your story?

- What is your characters greatest fear?

Both of these questions can cover the psychological such as being afraid of commitment or losing someone close or the physical, such as catching a murderer or being attacked.

In answering those two questions you have gone some way to establishing motivation. As motivation equals narrative action its a fundamental requirement.

Other areas for consideration may include;

- What is your character most ashamed of?

- Why does this characters lover/partner/family love or dislike them?

- What does your character think of him/herself?

- Is your character flawed in some way? (The great ones always are)

To a lesser extent your minor characters deserve the same attention. Complex supporting characters can make a good story, better.

Conflict

A plot must include a series of events which as we discussed last week leads to a climax and then a resolution. Everything leading up to the climax is called rising action, the series of events that your character/s faces in your story. They are the elements that drive your story forward so everything that you add to your story should move it forward it some way even if only indirectly.

In Gone With The Wind Scarlett OHara has a series of events to jump through: The civil war, the loss of the southern way of life, her descent into poverty, the loss of family and friends and the concern of losing her beloved property Tara. There are many battles for her to endure and in each we see a particular aspect of Scarletts personality coming to life. Once Scarlett and Rhett Butler marry (a climax) the story concentrates on falling action, that is everything that occurs after the climax and leads to the final resolution and Rhetts immortal words, Frankly my dear, I dont give a damn.

Foreshadowing is a technique of laying down clues and hints through a story that lead to later events or developments. Used carefully foreshadowing can increase reader involvement by creating a deeper context in which your story is set. For example if you were writing a novel in which a gun is used in a shooting by an unknown killer you could drop a clue early in the novel by showing a gun.

- An early scene in which the owner is seen polishing a hand gun diligently.

– May make the reader recall the scene and think the owner is the killer

- A scene in which a number of characters walk past a locked glass gun cabinet.

– May suggest to the reader that anyone could be the killer.

No matter how basic your clue or hint, keep it subtle. Building tension in your story by keeping your reader guessing as to the final outcome should be a major aim.

Did you imagine that Scarlett would marry Rhett and then subsequently damage her relationship with him to the extent that Rhett would leave her?

Where you really surprised when Scarlett straightened her back after Rhett slammed the door and said very slowly that she would return to Tara.

There is one major rule that is always important to have in the back of your mind show, dont tell.

Exercises.

If you wrote down some bullet points last week to describe the kind of setting you would like to place your story in you can use that as a background as you think about your characters.

- Write down two character names

- Write down five bullet points to briefly describe each one

- Describe what about human beings you find flawed or disappointing. Can you add these points to question 2. (Remember rounded characters are not perfect, unless the story calls for perfection).

- Describe the most beautiful part of the human body. Why is it beautiful to you? Can you include this in your character list, perhaps for a character who is not considered attractive?

- Now think about your two characters and your bullet point setting notes from last week. Consider the ways in which your chosen setting could determine/mould your characters personality and write about it.

Wow, you now have two characters and a setting see you next week.

Leave A Comment